It was Christmas Eve, but didn't feel like it in Vietnam.

The mess hall had been

unusually quiet. Although Christmas music was playing, nobody was talking.

Later, in the first platoon pilot's hooch, the mood was the same.

The recent

deaths of four pilots and four crewmen seemed to overshadow any chance of

holiday spirit.

Several pilots were sitting together, and one finally piped up, "We have to do

something happy to get out of this mood." Another offered that we should sing

Christmas Carols, but nobody would start the singing.

I announced that, after

almost a year of flying in Vietnam, I was not going to sit around there on

Christmas Day watching twenty long faces; I had to fly tomorrow.

After more silence, someone blurted out, "Let's take up a collection for the hospital at Dam Pao!" The thought was met with excited approval.

I suggested that

I would ask to fly the Da Lat MACV mission tomorrow to take the money that

we could collect tonight. Mike volunteered to fly with me.

First stop: the crew chiefs' hooch. I asked Bascom if he would like to fly the Da

Lat MACV mission. He and Dave quickly agreed, to also escape the prevailing

sad mood.

The company commander was in the operations bunker. I explained our plan but

he answered: "We don't have the Da Lat MACV mission. In fact, we don't have

any missions tomorrow. There is a cease-fire on."

I decided to beg: "Please, Sir, could you call battalion and see if some other

company has Da Lat MACV?"

The CO picked up the phone and then started writing on a mission sheet form.

He handed it to me and said, "Da Lat MACV helipad, oh seven thirty. We took

the mission from the 92nd." He took out his wallet, and handed me some money.

"Here's something for your collection."

When we reached the gunship platoon hooch, three pilots looked on sadly as one

man raked a pile of money from the center of a table towards himself. We made

our sales pitch about the hospital. The generous gambler pushed the pile toward

me and said: "I would just end up losing it all back to these guys anyway."

In one hooch, we were given a gift package of cheeses.

We decided to make

another pass through the company area, asking for cookies, candy, and other

foods.

As we left one hooch, the men inside started singing "Deck the Halls,"

and soon those in other buildings were competing. It wasn't clear whether the

competition was for the best, worst, or just loudest singing; but it was easy to see

that the mood of the company had changed for the better.

We next went to the mess hall. The mess sergeant and cooks were still there,

preparing for Christmas Day. The sergeant replied: "Do you have a truck with

you? We have too much food right now because of all the guys who went home

early. And we have some canned foods about to expire." One pilot went to get

the maintenance truck while the rest of us checked dates on cans and cartons of

food.

An infantry unit mess hall was not far away, so we went there next. We

accepted several cases of freeze-dried foods.

At the dispensary the medic gave

us bandages and dressings.

We tied down the pile of goods in the Huey.

After dropping off the truck the

four pilots walked back to our hooch. One pilot looked at his watch and said,

"Hey guys! It's midnight, Merry Christmas!"

My alarm clock startled me out of a deep sleep. A check with my wristwatch

verified the time, but something was wrong. Mornings were usually bustling

with the sounds of aircraft, trucks, and men preparing for the daily business of

war. Today there were no such sounds. Is this what peace sounds like?

In the shower building, Mike and I talked about what our families would be

doing today, half a world away. I reminded Mike that my wife promised me

another Christmas celebration, with decorated tree and wrapped presents, in just

two weeks. I would be meeting another Mike, my four-month-old son.

After breakfast, the others went to the flight line while I called for a weather

briefing.

When I got to the helicopter, Mike was doing the preflight inspection

and had just climbed up to the top of the Huey. Together, we checked the main

rotor hub and the "Jesus nut," named because, if it came off, "only Jesus could

help you." Everything was fine; we were ready to fly.

We took off and headed

for the mountains.

It felt good to fly with this crew; we were a finely-tuned team. Lee, who preferred the nickname "Bad Bascom," was the crew chief of this Huey; he did all

the daily maintenance on it and flew every mission. With Mike as co-pilot and

Dave as door gunner, we had taken that helicopter into and out of a lot of difficult situations.

Our company radio call sign was Polecat; we were Polecat three

five six.

I decided to climb higher than usual in the smooth morning air. As we left the

jungle plains along the coast, the green mountains of the Central Highlands rose

up to meet us. Fog on the plateau spilled over between the peaks, looking like

slow, misty, waterfalls. In the rising sunlight the mountain peaks cast long

shadows on the fog. The beauty and serenity of the scene was dazzling.

The mess hall had been quiet. The airfield was quiet. The radios were quiet. We

weren't even chattering on the intercom as we usually did. Our minds were all

with different families, somewhere back home, half a world away. Everything

was quiet and peaceful; it felt very, very, strange.

We landed at Da Lat, shut down the Huey, and walked into the bunker. The new

MACV senior advisor, a lieutenant colonel, agreed that we could stop at the

hospital at Dam Pao after we finished his planned route of stopping at every one of

his outposts. But we first had to meet a truck at Phan Rang Air Base.

|

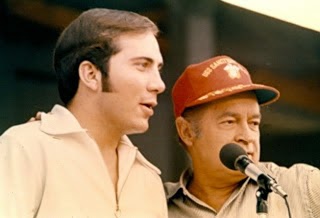

| Donut Dollies - Polecat 356 |

When we got close to Phan Rang, the whole crew listened as the colonel talked

by radio with his contact on the ground.

Not only was there food and mail to

pick up, but the colonel was asked if we also wanted to fly some Donut Dollies

around! The helicopter was filled with young men eagerly nodding their heads

and flight helmets, "YES."

Donut Dollies were American Red Cross volunteers, college graduates in their

early twenties.

Although no longer distributing donuts like their namesakes of

World War I, they were still in the service of helping the morale of the troops.

At large bases, they managed recreation centers; but they also traveled to the

smaller units in the field for short visits. For millions of GIs, they represented the

girlfriend, sister, or wife back home.

Soon we were heading back to the mountains with a Huey full of mail, fuel,

food, Christmas cargo, and two American young women.

We had sliced hot

turkey and pumpkin pies for the men who had been living off Vietnamese food

and canned Army-issue rations at the outposts.

When we got near the first outpost, the colonel, by radio, told the men on the

ground that we were going to make it snow. The Donut Dollies sprinkled laundry

soap flakes out of the Huey as we flew directly over a small group of American

and Vietnamese soldiers who must have thought we were crazy. Several of them were

rubbing their eyes as we came back to land. I'll never be sure if it was emotion or

if they just got soap flakes in their eyes.

The three Americans came over to the Huey as the rotor was slowing down. One

Donut Dolly gave each of them a package from the Red Cross and the other

called out names to distribute the mail.

After about 15 minutes of small talk between the Donut Dollies, the five MACV

soldiers, and the crew of 356, the colonel said, "We have a lot more stops to

make" and got back into the Huey. The soldiers stood there motionless, staring

at us as we started up, hovered, and then flew away.

At the next outpost, the colonel left us to talk privately with the local officials.

The crew and I didn't mind having the task of escorting the Donut Dollies. It

was easy to see how happy the soldiers were to talk with them. I wondered how

they were feeling. Their job was to cheer up other people on what may have

been their own first Christmas away from home; if they were lonely or sad, they

never let it show.

Throughout the day, the same scene was repeated at a number

of other small outposts.

Finally, when the official MACV work was done, we were above the hospital at

Dam Pao. Mike landed us a few hundred feet from the main building.

Several

American-looking men and women came out, carrying folding stretchers. They

first showed surprise that we were not bringing an injured new patient, and then

joy as we showed them the food, money, and medical supplies.

One woman

began to cry when she saw the price tag on a cheese gift pack. She explained

that twenty dollars could provide a Montagnard family with nutritious food for

more than a month.

One of the doctors asked if we would like to see the hospital. He talked as we

carried the goods from the Huey to the single-floor, tin-roof hospital building.

"Project Concern now has volunteer doctors and nurses from England, Australia, and

the USA. We provide health services to civilians and train medical assistants to do

the same in their own villages. In order to stay here we have to remain neutral.

Both sides respect our work, and leave us alone."

One of the women described a recent event. Two nurses and a medical assistant

student were returning from a remote clinic in the jungle when their jeep

became mired in mud. Many miles from even the smallest village, they knew

that they would not be able to walk to civilization before dark. A Viet Cong foot

patrol came upon them, pulled the jeep out of the mud, and sent them on their

way.

There were homemade Christmas decorations everywhere; most had been made

on the spot by patients or their families. Inside, the hospital reminded me of

pictures of Civil War hospitals. There were only a few pieces of modern

equipment but the hospital was very clean. The staff's living quarters were very

meager.

As we moved into one ward, a nurse gently lifted a very small baby from its

bed; and before I could stop her, she placed him in my arms. He was born that

morning. Although complications had been expected, the mother and baby were

perfectly healthy! As I held the tiny infant, I couldn't help but wonder how

I would feel in just two weeks, when I would hold my own four-month-old son for

the first time.

The staff invited us to stay for supper with them, and I could tell the invitation

was sincere. But the sun was getting low, and I didn't want to fly us home over

one hundred miles of mountainous jungle in the dark. I also would have felt

guilty to take any of their food, no matter how graciously offered.

As we started the Huey the colonel was still about fifty feet away talking to the

doctors and nurses. He took something out of his wallet and pressed it into the

hand of one of the doctors with a double-hand handshake, then quietly climbed

on board.

There was no chatter on the intercom as we flew back to Da Lat. Mike set the

Huey down softly. The colonel extended his hand towards me to shake hands.

"Thanks for taking us to that hospital, and Merry Christmas."

"Yes, sir, thank you, Merry Christmas."

The flights to Phan Rang and then back to Phan Thiet were also marked with

silence. I thought of my family that I would be with in just twelve days, good

friends I would soon be leaving behind, and good friends who would never go

home. I realized the unusual nature of that day.

In the midst of trouble and strife,

I would remember that one Christmas Day in Vietnam as a time of sharing, happiness, love -- and peace.

EPILOG:

At the 1993 dedication of the Vietnam Women's Memorial, I had forgotten

the Donut Dollies' names. Showing around a picture of them next to Polecat 356,

I found Ann and talked with Sue by telephone a few days later. That Christmas Day

was also special to them.

Project Concern International, 3550 Afton Road San Diego, CA 92123 is still

doing similar humanitarian work in Asia and several US cities.

Copyright 1993, by Jim Schueckler

“I am only one, but I am one. I can't do everything, but I can do something. The something I ought to do, I can do, and by the grace of God, I will.” ~Everett Hale

Feel free to comment on this post. You are also invited to write about anything you want to share. Memoirs From Nam is YOUR blog. You are writing America's history.

When Oliver Stone returned to the U.S., he was puzzled that the New Year's attack had received no media coverage.

When Oliver Stone returned to the U.S., he was puzzled that the New Year's attack had received no media coverage.

When Oliver Stone returned to the U.S., he was puzzled that the New Year's attack had received no media coverage.

When Oliver Stone returned to the U.S., he was puzzled that the New Year's attack had received no media coverage.

.jpg)